My interest in surfing began in the 60’s, when I saw a Surfer Magazine for the first time. Even though it took me a few more years to actually ride a wave, I was hooked on the beauty and nature of surfing.

As a young college student, I knew it was time to jump ship when I found myself in chemistry class with a copy of Surfer wedged into my textbook. I left and moved to the beach. That was a turning point for me, and life’s path was narrowed down to where it would lead me today.

Louie getting ready for a paddle at the Shoals in Rodanthe, 1974. Back then nearly everyone surfed at the Lighthouse, and bypassed our villages.

Louie getting ready for a paddle at the Shoals in Rodanthe, 1974. Back then nearly everyone surfed at the Lighthouse, and bypassed our villages.

I drifted into a network of friends that were also absorbed in the surfing culture. To us, it wasn’t a sport at all, but an almost spiritual way of life. Living carefree and day to day, we were essentially dropouts from what was typical America. Most of us weren’t looking for the two-car garage and the white picket fence dreams of most of our contemporaries. Waves were the most important thing, at times super-ceding jobs and even girl friends.

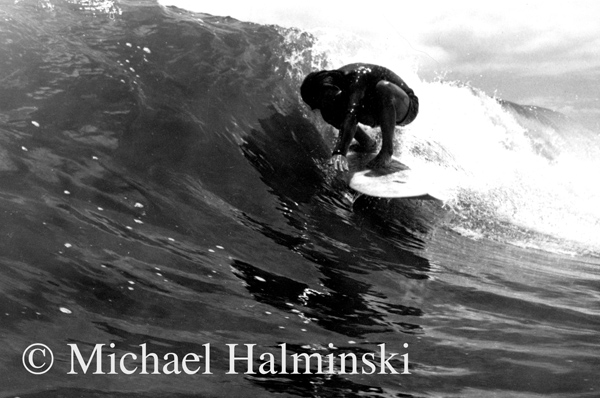

About 1968, I met Gary Revel at South Side, Indian River Inlet. His surfing took on a dynamic quality. He was among my new found surfing companions and could have easily gone into professional levels, but chose not to. We became life-long friends and still keep in touch. This photo of him cutting back at South Side was taken over 40 years ago, when I was just beginning to hone my photography skills.

About 1968, I met Gary Revel at South Side, Indian River Inlet. His surfing took on a dynamic quality. He was among my new found surfing companions and could have easily gone into professional levels, but chose not to. We became life-long friends and still keep in touch. This photo of him cutting back at South Side was taken over 40 years ago, when I was just beginning to hone my photography skills.

Louie Batzler at South Side circa 1970. We surfed and traveled together for many years. As a trained brick mason, he found us construction jobs that provided our income.

Louie Batzler at South Side circa 1970. We surfed and traveled together for many years. As a trained brick mason, he found us construction jobs that provided our income.

Mark Foo was a very young kid, but hung around the older surfers. He was very driven and loved surfing more than anything. He used to wake me up for dawn patrol by tossing pebbles at my bedroom window. He could be a pest at times. Mark went on to the Hawaiian Islands, became a world renown big wave rider, and a highly successful entrepreneur. In 1994, he tragically lost his life while surfing Maverick’s in California.

Mark Foo was a very young kid, but hung around the older surfers. He was very driven and loved surfing more than anything. He used to wake me up for dawn patrol by tossing pebbles at my bedroom window. He could be a pest at times. Mark went on to the Hawaiian Islands, became a world renown big wave rider, and a highly successful entrepreneur. In 1994, he tragically lost his life while surfing Maverick’s in California.

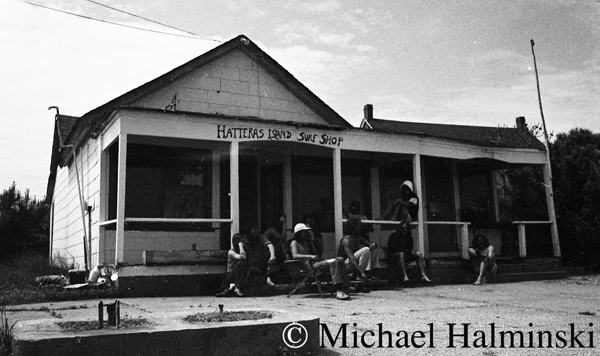

The gang at Barton Decker’s surf shop circa 1974.

The gang at Barton Decker’s surf shop circa 1974.

Summer of 1975, we gave these two hitch-hiking surfers a ride, while driving to Cape Hatteras Lighthouse for a big north swell.

Summer of 1975, we gave these two hitch-hiking surfers a ride, while driving to Cape Hatteras Lighthouse for a big north swell.

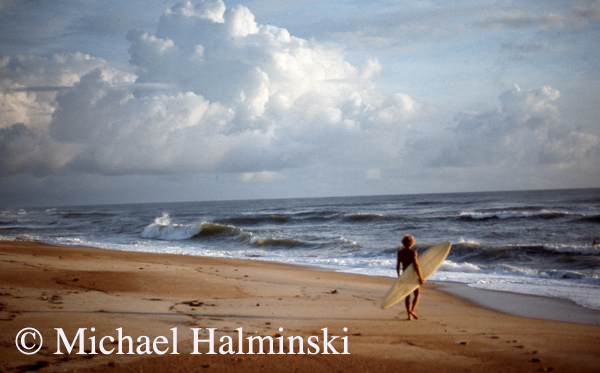

Mike Langowski, known as the Polock, rode his long boards even after board designs got shorter. 1977 photo taken at the lighthouse.

Mike Langowski, known as the Polock, rode his long boards even after board designs got shorter. 1977 photo taken at the lighthouse.

Dave Elliot and Jeff Ray checking the waves in the village of Waves. That was the first order of the day, to dictate what you did with your time. No waves, then you do something else, like go fishing or work on your broken down car. Dave was a stylish surfer, especially longboarding. Jeff was also a competent and well-traveled surfer. He later introduced me to Costa Rica in 1982.

Dave Elliot and Jeff Ray checking the waves in the village of Waves. That was the first order of the day, to dictate what you did with your time. No waves, then you do something else, like go fishing or work on your broken down car. Dave was a stylish surfer, especially longboarding. Jeff was also a competent and well-traveled surfer. He later introduced me to Costa Rica in 1982.

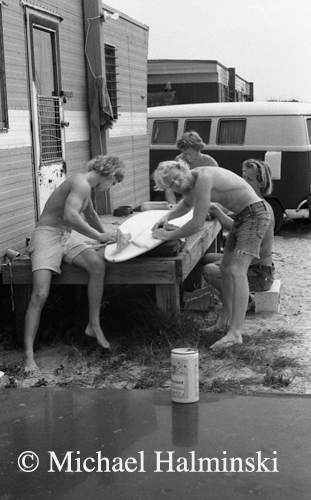

Robin, Bryant, Brent and Roger all pitch in to sand a hot coat on a board that I shaped for Roger. We lived in 2 trailers on the oceanfront in Waves. Little did we realize that there would be million dollar beach houses on this property 35 years later…. nor did we care.

Robin, Bryant, Brent and Roger all pitch in to sand a hot coat on a board that I shaped for Roger. We lived in 2 trailers on the oceanfront in Waves. Little did we realize that there would be million dollar beach houses on this property 35 years later…. nor did we care.

Brent Clark on a beautiful Pea Island wave in 1974. This secret spot had a hard bottom well offshore. From the beach, the waves looked much smaller than they actually were. It was a really long paddle, several hundred yards out, and broke like a reef point for about five years. It had some of the largest and best shaped waves that I ever rode, and only about 10 people knew about it.

Brent Clark on a beautiful Pea Island wave in 1974. This secret spot had a hard bottom well offshore. From the beach, the waves looked much smaller than they actually were. It was a really long paddle, several hundred yards out, and broke like a reef point for about five years. It had some of the largest and best shaped waves that I ever rode, and only about 10 people knew about it.

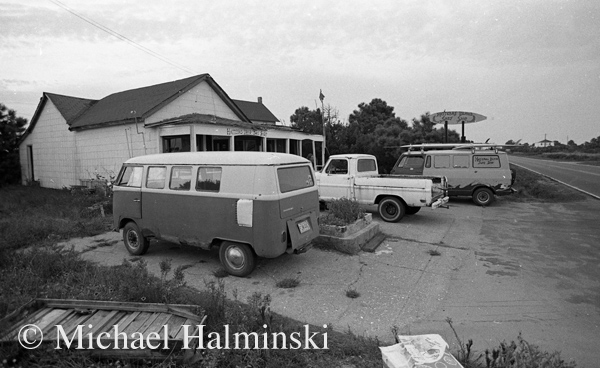

Classic car collection at the Hatteras Island Surf Shop.

Classic car collection at the Hatteras Island Surf Shop.

Another classic car ready to roll.

Another classic car ready to roll.

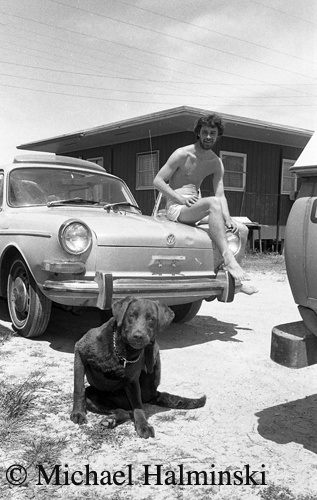

“Holly” waits for the next duck hunting trip, while Robin Gerald sits on his VW squareback, ready to find the next wave.

TO BE CONTINUED……