A hundred and six years ago today, one of the most daring rescues in Coast Guard history occurred. August 16, 1918 during World War l, the British tanker Mirlo exploded offshore after being targeted by a German U-boat. The crew at Chicamacomico Coast Guard Station launched their 25-foot surfboat offshore to where the Mirlo, loaded with fuel, was an inferno. Despite the danger, Keeper John Allen Midgett and 5 Surfmen maneuvered among the flames. Miraculously, they rescued 42 out of a crew of 51 and brought them to shore.

As a result, Captain John Allen Midgett, Zion Midgett, Arthur Midgett, Prochorus O’Neal, Clarence Midgett, and Leroy Midgett received highly prestigious awards.

All six men were decorated with United States Gold Lifesaving Medals.

In 1921, King George V of Great Britain bestowed specially minted Gold Lifesaving Medals to each of them.

July of 1930 the same lifesavers were awarded the American Cross of Honor. At the time only 11 had ever been given. Six of them belong to those men at Chicamacomico.

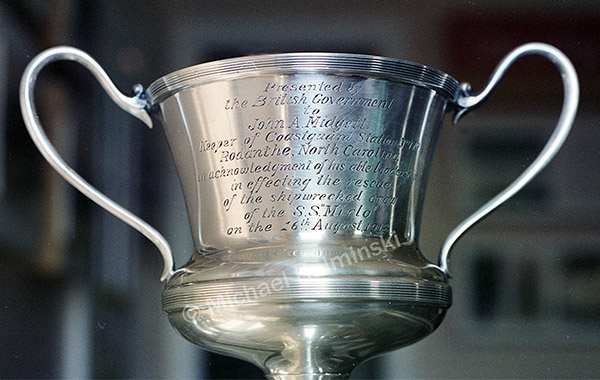

Captain John Allen Midgett was also presented a silver cup by the British Board of Trade.

As a past board member and president of Chicamacomico Historical Association, I kept personal photographic records of events at the station over many years. I photographed these awards in 1993, when we displayed them in celebration of the 75th anniversary of the Mirlo Rescue.

For a detailed account of this heroism go here:

https://chicamacomico.org/mirlo-rescue/