This is a time of year when new life is born to maintain a continuance of species. Signs are all around us. Much of it is obvious, as in nesting birds or budding plants. But much of it we cannot see, unless we look closely. Take the eastern oyster, for example.

For as long as I’ve lived on Hatteras Island, oysters have been a fascination to me. Whenever I go collecting, it’s apparent that they grow in certain areas more than others. I notice that even in those more prolific spots, that the oyster population has generally been in a steady decline. This is attributed to over-harvesting, water pollution, parasites and lack of substrate material for new oysters to attach and grow.

Mature brood stock oysters emit egg and sperm into the water column, which in turn combine to produce eyed larvae, the beginning of becoming a true oyster. A scientific collection permit has allowed me to gather brooders for my own oyster garden spawning. I also donate collected brood stock to the aquaculture program at Carteret Community College and to the University of North Carolina Coastal Studies Institute at Cape Hatteras School.

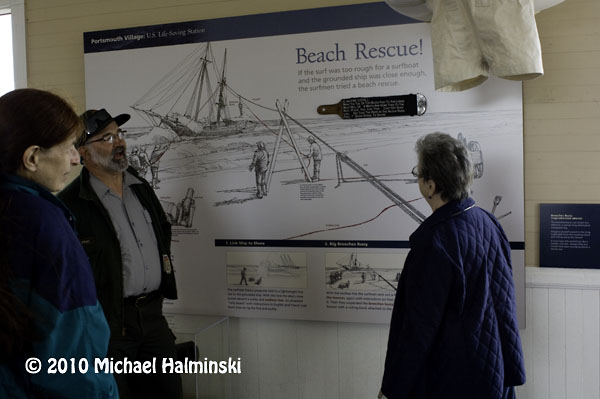

Several years ago I attended an oyster conference in Morehead City, where I saw a number of scientists and people like myself looking for answers. It was here where I met Dr. Kemp. He runs the aquaculture program at Carteret Community College. A number of us got together and founded Shellfish Gardeners of North Carolina. We are interested in growing oysters, not only as a recreational activity, but also as a way to help the environment. We have had workshops to learn more about life cycles, water quality and to educate others.

For oyster gardening in eastern Pamlico Sound, Skip Kemp has been my mentor.

This has evolved into a network of people compiling and studying data. I collect water quality data for the Citizen’s Monitoring Network out of East Carolina University, and also compile information for the Oyster Spat Monitoring Project based at University of North Carolina in Wilmington.

Past data indicates that now is a prime time for local oysters to be spawning, so I have to keep a sharp eye out to see if there are any new oyster spat.

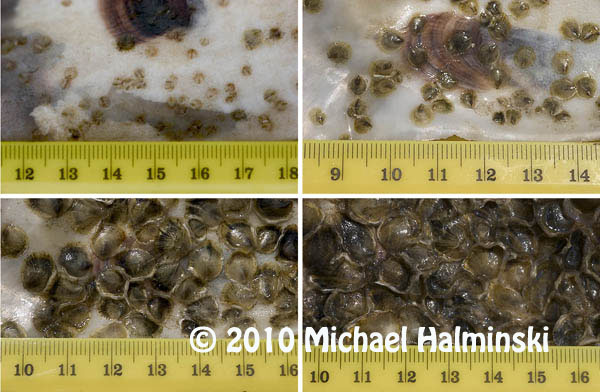

These eyed larvae have attached to an oyster shell and are 1 day old oysters.

This composite image shows new oyster spat at weekly intervals beginning with 1 week old at the upper left and 4 weeks old on the lower right. The initial growth rates are dramatic. The ruler scale is in centimeters.

These are almost 5 months old.

Yearlings can come in different sizes, depending on environmental conditions.

Looking out to Cape Point from the south or “the hook” side.

Looking out to Cape Point from the south or “the hook” side. Looking toward the point from the north beach.

Looking toward the point from the north beach.

Looking toward the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse from over the Point.

Looking toward the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse from over the Point. The shoreline of the pond at Cape Point.

The shoreline of the pond at Cape Point. No flight is complete without a lighthouse fly-by.

No flight is complete without a lighthouse fly-by. This is the site of the inlet that was cut by Hurricane Isabel.

This is the site of the inlet that was cut by Hurricane Isabel. The famous Hatteras Marlin Club in Hatteras Village.

The famous Hatteras Marlin Club in Hatteras Village. The south end of Hatteras Village at the ferry terminal to Ocracoke Island.

The south end of Hatteras Village at the ferry terminal to Ocracoke Island. The south point of Hatteras Island at Hatteras Inlet looking to Pamlico Sound.

The south point of Hatteras Island at Hatteras Inlet looking to Pamlico Sound. The ferry, Chicamacomico, en route to Ocracoke from Hatteras.

The ferry, Chicamacomico, en route to Ocracoke from Hatteras. The north end of Ocracoke Island at the site of the former Hatteras Inlet Coast Guard Station. The station was destroyed in storms. All that remains are the pilings. This illustrates the lack of stability of barrier island systems.

The north end of Ocracoke Island at the site of the former Hatteras Inlet Coast Guard Station. The station was destroyed in storms. All that remains are the pilings. This illustrates the lack of stability of barrier island systems. Ocracoke Island from the sound side.

Ocracoke Island from the sound side. An island in the sound behind Ocracoke Island.

An island in the sound behind Ocracoke Island. Silver Lake surrounded by scenic Ocracoke Village.

Silver Lake surrounded by scenic Ocracoke Village. The beautiful maritime forest at Springer’s Point on Ocracoke.

The beautiful maritime forest at Springer’s Point on Ocracoke. The untouched beach at Ocracoke’s South Point.

The untouched beach at Ocracoke’s South Point. A sandbar where Ocracoke Inlet meets the Pamlico Sound.

A sandbar where Ocracoke Inlet meets the Pamlico Sound. An underwater sand ridge extending into Pamlico Sound from Ocracoke Inlet.

An underwater sand ridge extending into Pamlico Sound from Ocracoke Inlet. A sandbar in the Pamlico Sound near Ocracoke Inlet.

A sandbar in the Pamlico Sound near Ocracoke Inlet. Dwight’s Cessna banking over Ocracoke Inlet for a shot at the untouched South Point.

Dwight’s Cessna banking over Ocracoke Inlet for a shot at the untouched South Point. The South Point of Ocracoke in a pristine state from 1,000 feet.

The South Point of Ocracoke in a pristine state from 1,000 feet.