Exploring the coast one may notice some curious artifacts. Some are natural and others are manmade. People collect shells, driftwood or beach glass. They’re all brought in by the sea. Some of my favorite collectables are the buoys from fishing nets and crab pots. They’re usually derelict from lost fishing gear and can be found at any time, but especially after storms.

I like displaying them from trees in my yard.

Some hang from an old trawl net that I found years ago.

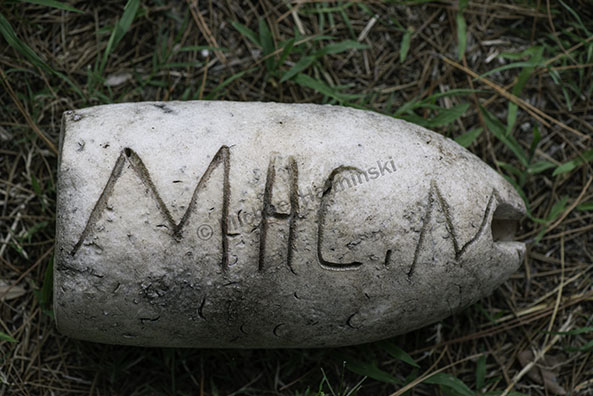

Some of them are very special to me, like this one that belonged to Mac Midgett.

I D Midgett is my next door neighbor and has fished all his life.

Another buoy belonged to my good friend and neighbor Eric Anglin. He still brings me fish.

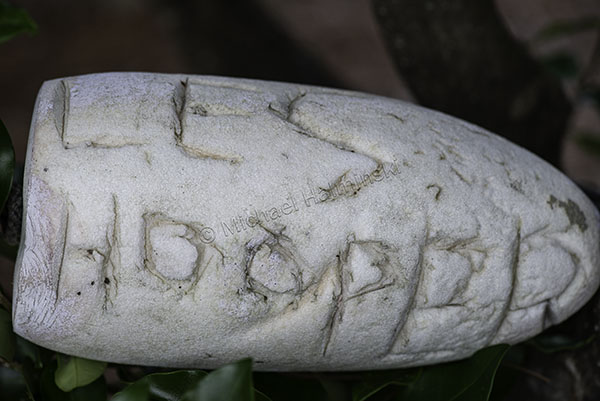

Recently this gem was given to me by Steve Ryan. It was Les Hooper’s buoy. Les and Steve were neighbors. Les is gone now, but his spirit remains.

I also have a buoy from Rudy Gray of Waves. He no longer fishes commercially, but is still an accomplished angler.

A few months ago I got a call from Roger Wooleyhan who fishes commercially in Delaware. His fishing buddy, Layton Moore has another fishing friend who came across this buoy in his net near Ocean City, Maryland. It’s a crab pot buoy that belonged to my friend Asa Gray also of Waves. Asa passed away about 2 years ago, and he was Rudy’s brother.

I can only imagine how this arrived so far away. It’s reminiscent of a message in a bottle. It must have flowed from Pamlico Sound into the Atlantic, up the coast and through Ocean City Inlet and on to Isle of Wight Bay. Maybe it hitched a ride snagged to a rudder. At any rate, that’s some journey!