Robin was a great storyteller. Some seemed lavishly embellished, but many were true. Being Robin’s occasional co-conspiritor, I had the chance to see some of these exploits first hand.

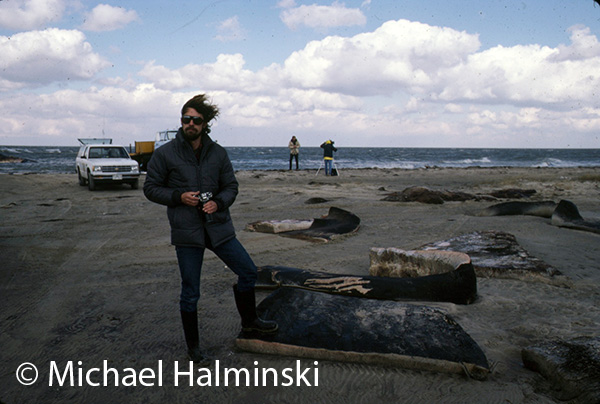

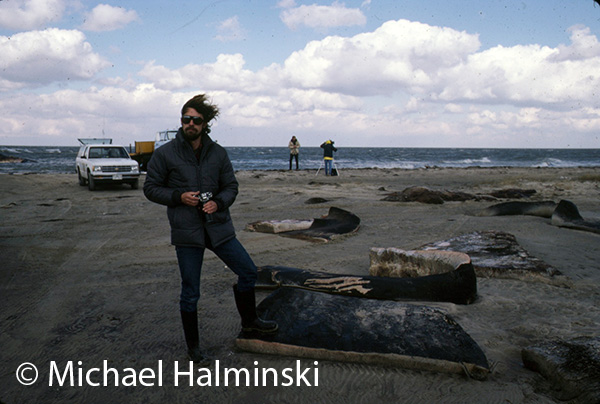

One cold January morning in 1987, Robin came to my house to pick me up for an exploratory road trip down the island. A dead sperm whale had washed up and experts from the Smithsonian were on site at the South Point performing a necropsy and taking body parts. By the time we got there, the area was littered with huge chunks of blubber and someone from the media was taping a news release of the event.

We looked around, and took some photos. When we had enough, we got back in his trusty, rusty Toyota truck. It was then that it struck us how badly we smelled. The whale oil that permeated the beach was now on our boots. We got a good chuckle out of that and drove along the pole road towards Hatteras Village. Again we stopped on the beach to look at some shells and driftwood.

Then from out of nowhere came a honking canada goose pitching in nearby. The goose landed behind a sand dune about a hundred yards away. Robin’s eyes lit up, and he had “dinner” written all over his face.

Robin had a shotgun behind the seat and didn’t waste any time retrieving it. He crept up to the dune where the goose had landed. As I had witnessed many times before, he jumped up quickly, and was ready to fire. The goose was nowhere to be found. We looked everywhere for signs, tracks, anything to prove to ourselves that this really happened. We found no trace to verify what we’d just witnessed.

By that time it was late in the afternoon and we drove the beach toward Cape Point. Robin had hunting on his mind and was determined to bring home the bacon. He knew right where to go in Buxton Woods.

When we got there, near a large shallow pond known as the Dynamite Hole, Robin proceeded to wade in above his knees. He was out of sight when I heard a shot. He reappeared, walking toward me holding one of his favorite things, a nice black duck. He stashed the duck in the back of the truck and said he was going back to get something else. This time I heard another shot, and like the last time, he reappeared. This time to my surprise, he was holding a swan.

We hightailed it out of there and when we got to my house, he cleaned the black duck for supper. Then in somewhat of a spiritual experience, he took out the heart still warm with life, seared it in a skillet, cut it in half and we ate it. It somehow gave us a burst of energy, and we consumed the rest of the duck.

Dick Darcey, my neighbor next door, came over to see what the commotion was all about. Dick was an avid “by the book” hunter and was shocked to see all this in front of him. He knew, not only hunting a swan was against the law, but also hunting season had ended the day before.

As with many of Robin’s exploits, the story got new life in future revelations, and become known to us as the day of the disappearing goose.

Flocks feed voraciously in the cedars around my house.

Flocks feed voraciously in the cedars around my house. The tail is striking and looks as if it was dipped in yellow paint.

The tail is striking and looks as if it was dipped in yellow paint. The name of the bird comes from the waxy red secretions found on the tips of the secondary feathers.

The name of the bird comes from the waxy red secretions found on the tips of the secondary feathers.